My ARCH colleagues’ latest findings in Kathmandu Valley, Nepal reveals some good news that the prevalence of mother-child dyads suffering from coexisting multiple burdens of malnutrition is still relatively low. A little over 8 percent in their study sample were an overweight mother with an undernourished child (“double burden”), and only about 3 percent were an overweight mother whose child was affected by stunting, wasting or underweight as well as iron deficiency (“triple burden”).

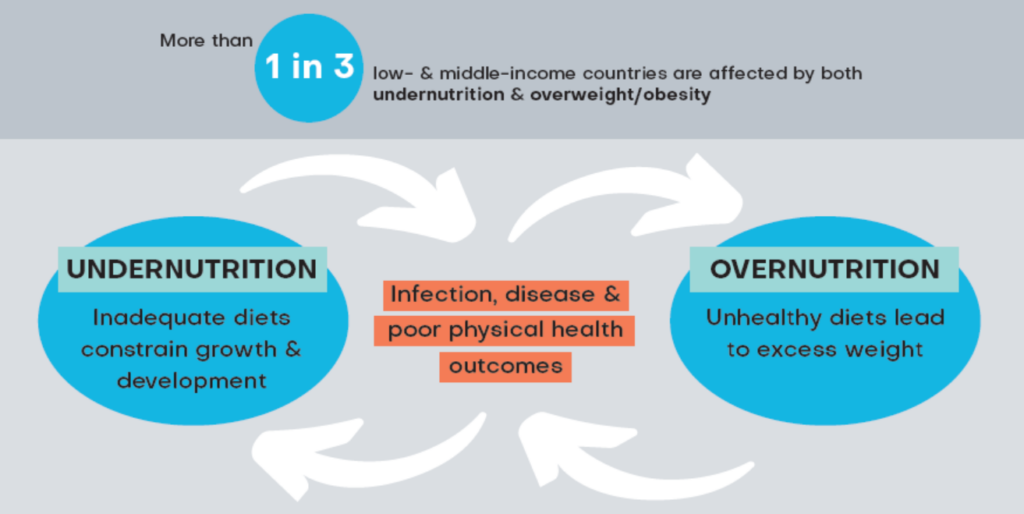

Unfortunately, there is still plenty of malnutrition in other forms present in these Kathmandu Valley households. While there has clearly been great progress in reducing child stunting, rates remain high, and iron deficiency anemia is impairing the cognitive and physical development of almost one third of these children. But perhaps most alarming, overweight and obesity is now affecting just under half of mothers. And data for the country as a whole suggests that the double burden is indeed a serious problem.

Epidemiologists refer to this phenomenon as the nutrition transition. Globalization brings supplies of industrially produced ultra-processed foods into low and middle-income countries and replaces traditional diets – which may be nutritionally insufficient but are nonetheless comprised of whole foods like vegetables, grains, and pulses – with products high in added sugars, fats, salt, and chemicals and shorn of fibers and micronutrients. This kind of product is often low cost, easily overconsumed, and displaces healthier foods.

The health risks of these changing diets are compounded in urban areas by more sedentary lifestyles. It has also been shown that those who have been undernourished in utero or during the first two years of life are programmed to be more susceptible to developing chronic diseases like diabetes and cardiovascular diseases, as well as to weight gain. We have also seen how these conditions also make people far more vulnerable to dangerous complications of COVID-19. We are likely heading towards a perfect public health storm.

It is abundantly clear that these problems are not just driven by individual choice but also by the conditions created by the wider food environment. When foods are manufactured to be hard to resist, especially for those living in poverty and suffering chronic stress, when they are convenient to eat at any time, when they are less expensive and more easily accessible than fresh foods, and when children beg parents for them, the decks are stacked against healthful eating.

There are, perhaps, ways to navigate away from the storm. A number of governments have shown there are ways to reshape food environments with policies that help consumers make better choices. In the face of their own burgeoning problems of overweight and obesity, Chile, Mexico, and Peru have used various combinations of warning labels, taxes, and advertising restrictions on unhealthy foods and beverages, and these actions have steered consumers to buy less of them. These changes are small, but they are a move in the right direction. They are also nudging food companies to take some steps towards developing healthier options.

A recent Commission of the journal The Lancet connected the convergence of undernutrition and obesity with another looming threat, climate change. The publication described the current situation as a global syndemic, or multiple, intertwined epidemics. The authors show how the three crises have common drivers; for example, the industrial food system contributes to obesity and greenhouse gas emissions, and climate change will exacerbate malnutrition. While they see policies as part of the solution, they also call for a more ambitious goal: a global Framework Convention of Food Systems modeled after the global agreement to regulate tobacco. National governments could come together to agree on a legal structure based on the ideals of human rights for health, food, and safe environments. A global consensus might just be strong enough to drive industry and governments to redesign the entire food production, promotion, and distribution system.

Ambitious, yes. Idealistic, certainly. But it may require nothing less to transform our food system into one that nourishes humans and preserves a livable planet – and protect countries like Nepal from double and triple burdens of malnutrition.

About the guest writer:

Jennifer Nielsen, PhD is Senior Nutrition Advisor at Helen Keller International where, since 2006, she has provided technical guidance to nutrition and health programs in sub-Saharan Africa and South and East Asia. Before that she served for ten years in the US Agency for International Development, posted in Côte d’Ivoire, Egypt and then Washington, D.C.